In 1978 I graduated at DAMS in Bologna with a thesis entitled John Cage and Merce Cunningham / Theatrical music and American dance for a musical theater. My thesis supervisor was Giampiero Cane. The president of the panel was Umberto Eco and I kindly remember Roberto Leydi among the committee members and other illustrious personalities of the time.

The appendix of my work featured a talk I had with John Cage after his famous performance at the Teatro Lirico in Milan, a concert that stands as a breakthrough in the activities promoted by what was then called the Movimento (Movement).

Luckily that night I had brought with me an archaic tape recorder and the tape of the conversation between me and John Cage is still preciously archived in my vaults. On this note, I would like to thank my friend Giovanni Carpano whom I haven't heard for so many years and who shared with me the long trip from Cesena as well as the troublesome approach to Cage which had started the afternoon before the concert.

What follows is the transcription of the appendix as it was typed in my thesis. I have just edited the text while listening to the tape again, although basically everything appears here unaltered. Obviously the historical importance of concert at Lirico was not clear yet.

Maurizio Comandini – Cesena – November 6 2007

p.s. The incautious journalist that I anonymously cited in the text is the ineffable Mario Marenco, a 'mosquito' that accompanied us throughout the whole evening. I kindly remember his attitude...

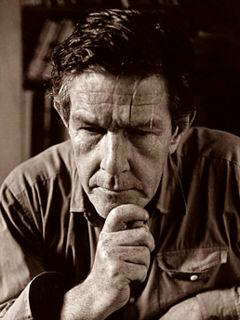

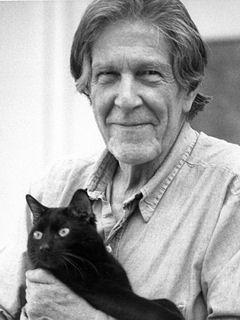

The interview with John Cage below, took place in the evening between December 2nd and 3rd 1977, after his concert at the Teatro Lirico in Milan.

Cage, whom I had spoken to for few minutes in the afternoon, kindly invited me to follow him at Frankestein, the club that the concert promoters had unluckily chosen as the ideal place to relax after the performance.

Therefore the recording of the conversation was affected by the 'infernal' music that was overwhelming us all the time, so the transcription is a bit incomplete.

I would like to remark the extreme kindness of John Cage who, despite of my poor English, tried to understand my questions and give intelligible answers.

Because of the location, not exactly ideal, the conversation consisted of an exchange of information on our respective works, focusing more of course on his ones than on mine.

(in the background a dance arrangement of the Star Wars soundtrack)

MC: I'm very interested in your works with Merce Cunningham, because I see your work from the point of view of the theatrical involvement in the arts: A) your music is theatrical; B) the entire situation of your music and Merce's dance is theatrical. Do you think this is the right point of view?

JC: (while eating whole wheat rice) ...I think it's a good point to start from. And instead of having the dance support the music or the dance express the music, we coexist.

MC: And what about the other structures of the performance? For example, the light, the décor and so on: are they equal parts of the whole thing?

JC: They are, sure. Particularly the light. But so far I don't think that the light has been as an active part as the dance and the sound. For this reason: when one sees the dance and if the light plays a lively part, there would be parts when you wouldn't be able to see it. Therefore, you transform the light not into an art but into a utility, to make it possible to see the dance.

MC: It seems like there are some defined periods of your collaboration with Cunningham. I think the first period is until 1952, sort of 'classical' period, in the avantgarde of course. A classical period due to the sense of loneliness. There are lots of solo parts in those dances.

JC: The Company begins later.

MC: Later, in 1952.

JC: It begins a little bit before 1952. Merce worked with a smaller group of people he put together for the time needed to set up a choreography, but it already was a group work. For instance, the Sixteen Dances for Solo and Company of Three or The Seasons.

MC: Right, and in Sixteen Dances, Cunningham begins to use chance procedures that seem to be the sign of the second period, from 1952, the beginning of the Cunningham Dance Company, to 1964, at the end of the world tour.

JC: Until the partial break-up and reforming of the Company.

MC: It seems like chance operations were the distinctive feature of your work in this period.

JC: They still are.

MC: Sure. What I wanted to emphasize is the different approach to the dance praxis, which determined Rauschenberg's presence, up to his leave and the arrival of Jasper...

JC: Johns, sure.

MC: Carolyn Brown's words in the book by James Klosty on Cunningham are very clear about the issues caused by all of that.

JC: It was a hard time. I know that book, it's very nice.

MC: It is a precious source of information on Cunningham: it is less easy to find information about him, than about you in Italy.

JC: It's a shame.

MC: Do you still work with Merce?

JC: I don't travel with them anymore. But I keep on writing music for them. The last piece was in September. It's called Inlets. The body goes in the water. Both the decor and the costumes are filled with water (smiling).

(short break caused by some people, among whom I remember Valeria Magli, that say goodbye to Cage before going home)

MC: What do you think about the idea of using the space of musical theater as a vital space for a revolution in the arts, in the collective life? An empty space in which a multitude of signs and possibilities get together. I believe it's one of the most appropriate spaces where to think and start a revolution.

JC: It's a wonderful idea, I know what you mean. You mean a space that besides containing movement and sound, can also contain other things with no discrimination, no prejudices, no boundaries. I agree with you.

MC: It's one way to look at it...

JC: Yes, I agree. This is the beginning of theater, since its significance is unlimited, to the point that the notion of everything happening at the same time it's not only theatrical, but also religious. When I say religious, I mean the complexity of creation. It's almost like what happened tonight during the concert: the audience was in the right mood, there were strange things, but they worked well. The opposites coincided. (footnote 1)

MC: I think it was a typical indeterminate situation because...

JC: yes (laughing)

MC: ...you didn't have the chance to...

JC: ...control...

MC: Yes. And it was clear to everyone, therefore no one could speculate on it. I believe tonight's feeling was the risk, the indetermination and I think it was an interesting experience for me, but for you too.

JC: Yes, sure (laughing aloud)

(short break caused by a brief interview with a Rai tv journalist whose unique preoccupation was to discover, trying not to openly reveal it, whether Cage had Jewish origins or not)

MC: Do you still work with David Tudor?

JC: No, David is completely devoted to electronic music now, whereas I am busy with music for violin. We're still friends, but he's focusing on his own work and he doesn't play piano music anymore. However, he will perform two concerts of my music, on December 21st and 22nd in New York.

MC: It's interesting to notice in your work, the return to the music for voice in the 70's after having abandoned it at the end of the 30's, apart from sporadic episodes. It might be a way to interpret...

JC: Yes, yes.

MC: It's a return to the primary instrument.

JC: I am moving towards the violin now.

MC: Do you play the violin?

JC: Nope, it's an absolute mystery for me (laughing).

MC: Do you think that skill is important?

JC: What kind of skill?

MC: Do you think it's important for a musician to be skilled?

JC: Do you mean to compose or to perform?

MC: To perform. Actually, to the performance that at the same time is a composition. In other words, to the improvisation.

JC: Skill is very important. Sometimes it's really necessary, some other times it isn't. When you possess it – let's consider Demetrio (footnote 2) for instance, he's a great singer and he has a great control of the vocal chords, he knows them much more than I do. And there is another singer, really amazing, who is exploring the possibilities of the voice, Joan La Barbera. Even Cathy Berberian doesn't have such a full control of her voice like these two singers. I am also exploring the voice, without possessing the skill however.

MC: I think it's the most interesting way to explore the voice, or any other instrument.

JC: Either way, we can obtain results, explanations.

MC: I believe it's important to begin to think like first-time musicians, as if it were our first approach to the instrument.

JC: It would be very interesting.

MC: I am thinking of a musical theater context in particular. It's one of the possibilities that this place offers.

JC: Sure. This is all very interesting, very right... Are you writing a book?

MC: No, I'm just writing my thesis...

JC: You have a beautiful mind. How will you develop your intuitions?

MC: I don't know. The social and political situation in this country is quite complicated.

JC: When the social context is negative, people get better (big laugh).

(at this point Cage started to kindly ask me about my work, explaining the problems of working in the arts for ten minutes approx. Cage was so nice that he even recommended me to Gianni Sassi, to whom he asked if he could have helped me to find a job in the initiatives that Cramps Records was promoting then)

MC: What can you tell me about Erik Satie today?

JC: Je l'aime. Some writings of his have been recently published, Ornella Volta gathered them. The book is called Ecrits. It's beautiful. It has been published by Chant Libre Editions.

(more interruptions followed: people saying goodbye and going away. I stopped the recorder and continued to converse with Cage and the other people next to us. I talked to Cage of the interview he had given to Michael Zwerin, in which jazz music was mentioned and I discovered that Cage was a little bit more open to the positions of the new Afro-American music (he had changed, not the music). He told me he was friend of Anthony Braxton and of other musicians of the Chicagoan scene. He told me about a funny anecdote about the Art Ensemble of Chicago quoted, Water Marchetti – who had translated it – said, in the upcoming For the Birds volume. It would be released in January 1978 and it is a great tool to investigate Cage's work. At 2am the conversation ended and we said goodbye)

(1) The concert at Teatro Lirico featured intense and ferocious moments, because of people occupying the stage in order to disturb Cage's performance. They took his glasses off, they turned the light off and so on. It was the promoters' fault, since they had been advertising the concert like a pop show to entice a wider audience.

(2) Demetrio Stratos was there while the interview was taking place, even if at another table with the other concert promoters.

Menu

Menu